The story behind the making of bronze sculptures of Georgia Tech's first African American students and first African American graduate.

In summer 2018, Rafael L. Bras, Georgia Tech provost and executive vice president for Academic Affairs and the K. Harrison Brown Family Chair, turned to Atlanta sculptor Martin Dawe.

Months earlier on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the Institute dedicated Dawe’s Continuing the Conversation interactive art piece in Harrison Square, depicting Rosa Parks at age 42 in 1955 — the year her courageous act of refusing to give up her seat for a white passenger on a Montgomery bus helped launch the yearlong Montgomery bus boycott — and at the age she died, 92. The pieces sit across from each other, an empty seat in between, inviting passersby to sit in reflection.

Bras shared an idea for a second campus sculpture collaboration.

The provost had received a call from Francis S. “Bo” Godbold (IE 1965) with an idea to have a statue dedicated to Ford C. Greene, one of three African American students who integrated Georgia Tech in 1961. Godbold, who led a successful career in the financial services industry after graduating from Tech in 1965 and Harvard Business School in 1969, had shared a class with Greene.

His idea eventually developed into a having a sculpture of all three of Tech’s first African American matriculants – Greene, Ralph A. Long Jr., and Lawrence M. Williams – dedicated and installed on campus grounds. The men made their arrival on campus in September 1961, less than five years after the bus boycott in Montgomery ended.

“When the three of us were shepherded in, the [Georgia] State Patrol had to escort us everywhere we went,” reflected Long on the 50th anniversary of the integration.

In 1961, Georgia Tech became the first major university in the Deep South to open its doors to African American students without a court order.

The Three Pioneers

“This project was different than Continuing the Conversation,” said Dawe, founder and owner of Cherrylion Studios in midtown Atlanta. A graduate of Georgia State University, Dawe apprenticed for eight years with Georgia Tech alumnus, architecture professor, and sculptor Julian Harris before his death in 1987.

“With Rosa, I was the conductor,” Dawe continued. He came up with the idea for Continuing the Conversation years ago and shared it with Bras and then-director of Tech’s Office of the Arts Madison Cario who both felt the piece would be a perfect fit for the campus. “With this project of these three pioneers, however, the score was written for me by Bras and Godbold.”

The first step was to talk with the men.

“After talking with them and getting their approval on the project, we decided that the iconic photo of the three on their first day on campus would be my starting point,” Dawe said. “I then studied various photos of each of them from that time.”

He continued, “I really liked the idea of a walking sculpture which would add sense of comradery to its feel. With this sculpture, they’re all looking off [to their left] and you get this sense that they’re looking at something, but you don’t know if it’s [something] good or bad. For me, that tells a little bit of what they went through on campus – that they had this awareness, a very strong awareness about what was going on around them.”

According to Archie Ervin, vice president for Institute Diversity, “These were three individuals who, though not members who were readily accepted into the community, were very proud to be at Georgia Tech. Even then [their first day on campus] they were wearing their Georgia Tech insignia.”

It was quickly decided that the statue would be placed in Harrison Square, named after Edwin D. Harrison, Georgia Tech’s sixth president (1957-1969). The campus’ integration came under Harrison’s watch just one day after he called a meeting of students and ordered that the integration be done peacefully.

On the day of the pioneers’ arrival, Harrison flew overhead the campus on a plane to observe its climate. He also evacuated his family from their home due to a barrage of threats.

The First Graduate

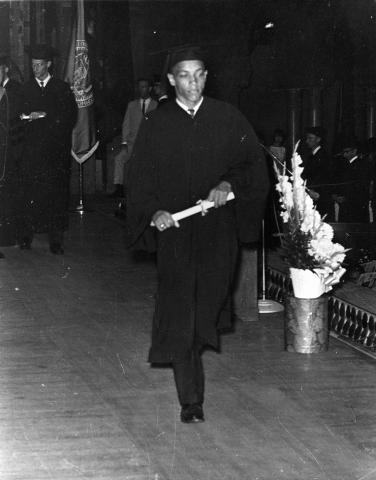

Months later, in February 2019, the idea to also dedicate a bronze sculpture of Tech’s first African American graduate Ronald L. Yancey (EE 1965) was developed.

“Yancey started after the three pioneers, but he was the first to graduate, so it didn’t seem fair to not include him as a part of this story,” said Dawe.

Yancey, who entered Georgia Tech in September 1962, one year after the campus’ integration, completed the first two years of his undergraduate degree at Morehouse College. During those years, he applied repeatedly to Tech, with no answers provided with each denial despite excellent grades and test scores.

Once accepted, Yancey faced isolation and intimidation on campus.

“It was a lonely and difficult time,” said Yancey. “‘Glares and stares’ is the best way I can put it, but I try not to reflect on the negative.”

Though Tech exempted seniors from final exams at the time, Yancey was required to take 18 exams in his five classes during his last three weeks of school. He would prove successful and graduated with a degree in electrical engineering in 1965, becoming the Institute’s first black graduate.

With the target of dedicating both statues on campus later that September, Dawe and his team immediately went to work on the Yancey statue.

But where would the Yancey piece go?

There were almost a dozen locations around campus discussed before the decision was made that it would be installed in the Wayne G. Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons, seated at the bottom of the atrium’s wooden staircase providing the building's one million yearly visitors with an interactive seating experience much like Parks’ Continuing the Conversation.

“The bronze pieces take at least four months to complete: a month to complete the molds and then they spend about three months at the Baer Bronze Fine Art Foundry in Springville, Utah,” said Dawe.

At the foundry, the sculptures were then bronzed, welded, and sandblasted.

The final stage of the process is patina -- the coloration of the bronze brought about by the oxidation of the metal surface. This is achieved by applying various chemicals and finishes to the surface of the bronze until the desired color effect is reached. For both the Three Pioneers and the First Graduate, Dawe decided on an ombré effect from top to bottom.

The Trailblazers

“These pieces are reminders that it wasn’t that long ago when intolerance ruled the day,” said Bras.

“The other part of the lesson that I hope doesn’t escape people is the reality is that these young men must have lived through very difficult times,” Bras added. “Despite the fact that our intention was to integrate peacefully, nobody is naïve enough to think that this was an easy time for them.”

He added, “What I hope is that as the community interacts with these pieces – either walking or sitting next to them – that their interaction will become natural. They’re reminders of how far we have come. They’re also reminders that we still have a way to go."

Life After Integration

Greene studied chemical engineering at Georgia Tech. He completed his bachelor’s degree in mathematics and computer science at Morgan State University and led a successful career in telecommunications and information technology systems.

After attending Georgia Tech, Long completed his bachelor’s degree at Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University) in mathematics and physics and would go on to become the first African American systems engineer for the Large Systems Group in the southeastern U.S. at IBM Atlanta.

Williams was drafted and served honorably in the Vietnam War, earning several distinctions and honors.

One week after graduating from Tech, Yancey moved to the Washington, D.C. area. He went on to have a successful career with the Department of Defense and served on the Georgia Tech Alumni Association Board of Trustees.

The four men will participate on a panel at the Institute’s 11th Annual Diversity Symposium, Georgia Tech’s Racial Diversity Journey: Recognizing Our Past, Acknowledging Our Present, and Charting Our Future, on September 4.

Later that afternoon, both sculptures will be unveiled and dedicated in their honor at Trailblazers: The Struggle and the Promise in Harrison Square.

Additional Images